Coroutines Job Structures

Featured in Android Weekly #447 & Kotlin Weekly #231

As you use coroutines in different use cases, understanding the relationship among the Jobs you’re creating is essential. The relationship determines how the library will cancel your coroutine Jobs. This article will explore examples of creating Job hierarchies, their effect on cancellation, and Supervisor Jobs.

Problem

Assume we’re using coroutines Android. You may have a setup of a view model that is launching a coroutine. Inside the coroutine, you may launch other coroutines to do different kinds of work. There are various ways to launch coroutines which have different consequences.

class MyViewModel(

repo1: MyRepository1,

repo2: MyRepository2

): ViewModel {

fun getData() {

viewModelScope.launch {

launch { ... }

launch { ... }

repo1.getData()

repo2.getData()

}

}

}

class MyRepository1 {

val coroutineScope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

fun getData() {

coroutineScope.launch { ... }

}

}

class MyRepository2(

val lifecycleScope: LifecycleCoroutineScope

) {

fun getData() {

lifecycleScope.launch(Dispatcers.IO) { ... }

}

}

In the example above, the view model launches a coroutine on the view model scope. It does so using a launch block. It also communicates with two repositories. The first repository creates a scope internally and launches a coroutine on it. The second repository has a lifecycle scope injected and launches a coroutine on it.

We are building coroutines that have a relationship with one another. Some of them are outliers that standalone. These approaches affect how the library cancels the workers during clean-up or when an exception occurs inside the coroutines.

Coroutine Hierarchy

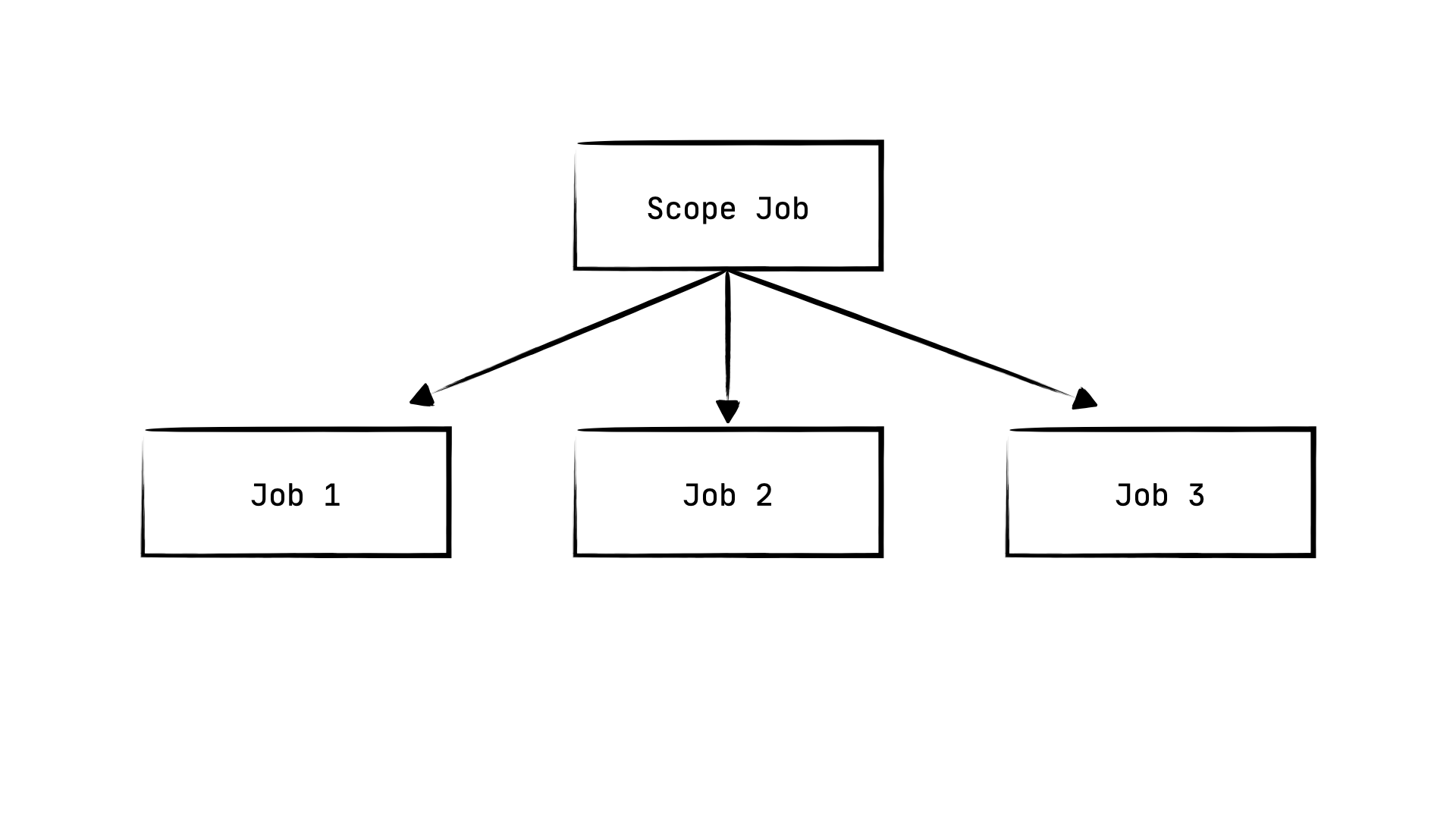

Assume we have a scope on an IO dispatcher. We launch three coroutines on the coroutine scope.

val scope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

// scope.coroutineContext[Job]

val job1 = scope.launch { ... }

val job2 = scope.launch { ... }

val job2 = scope.launch { ... }

In this simple example, there are four different jobs created. Each launch call returns a Job. The scope itself also has a Job. We could access the scope’s Job from its context.

scope.coroutineContext[Job]

These Jobs have a relationship with one another. The scope’s Job is the parent of the three launched jobs.

Job Cancellation

The relationship between these coroutines affects cancellation.

val scope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

val job1 = scope.launch {

while(isActive) { delay(2000) }

}

val job2 = scope.launch {

while(isActive) { delay(3000) }

}

val job2 = scope.launch {

while(isActive) { delay(3000) }

}

delay(1000)

scope.cancel()

In the example above, each child coroutine is doing some work while checking it is active. Canceling the scope will iterate through each child of the scope’s Job and cancel it.

Nested Coroutines

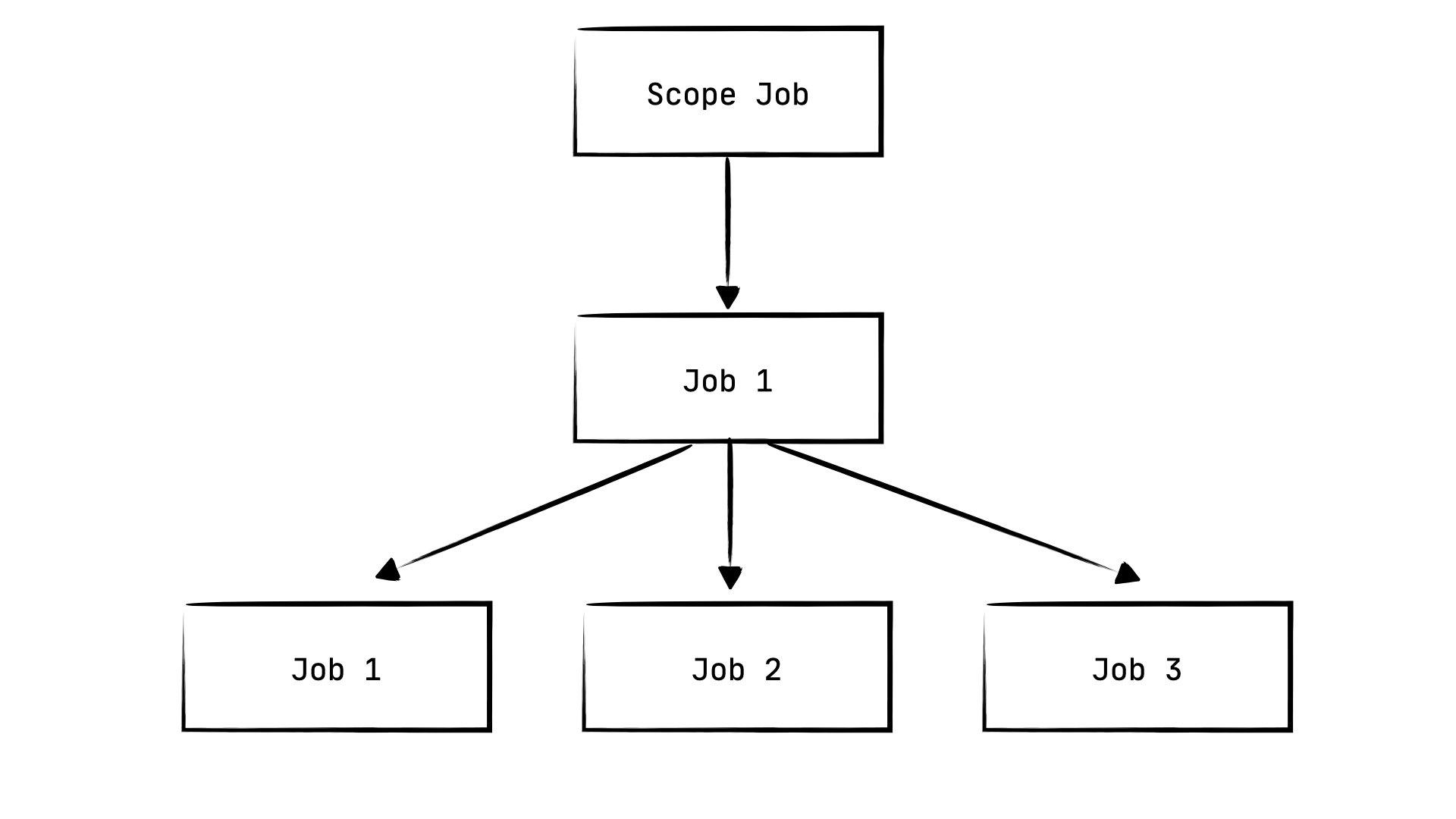

As we are working with coroutines, we could build complex structures with nested coroutines.

val scope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

val job = scope.launch {

val job1 = launch {

delay(2000)

}

val job2 = launch {

delay(3000)

}

val job3 = launch {

delay(4000)

}

}

In this example, we’re launching a coroutine on the scope. Inside this coroutine, there are three child coroutines launched. Each coroutine delays by some milliseconds. These three coroutine’s Jobs are grandchildren of the scope’s Job.

We could print out the number of children a Job has.

scope.coroutineContext[Job]?.children?.count() // 1

In this example above, the scope’s Job will have one relationship: the launched coroutine. The launched Job has three child Jobs.

job.children.count() // 3

We could traverse the hierarchy of Jobs in each depth of the nested hierarchy.

scope.coroutineContext[Job]?.children?.forEach { job ->

// launched job

println(job)

// grandchildren

job.children.forEach {

println(job)

}

}

Nested Coroutines Cancellation

If we were to cancel the scope’s Job, it will propagate down and cancel all its grandchildren.

val scope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

val job = scope.launch {

val job1 = launch {

delay(2000)

}

val job2 = launch {

delay(3000)

}

val job3 = launch {

delay(4000)

}

}

scope.cancel()

As you launch coroutines, you may create a coroutine on a different scope. It is essential to understand the implications.

val scope1 = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

val job = scope.launch {

val scope2 = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

scope2.launch { ... }

val job1 = launch { ... }

val job2 = launch { ... }

val job3 = launch { ... }

}

scope1.cancel()

In the example above, the launch block creates a standalone coroutine. This coroutine is not part of the existing coroutine hierarchy. It’s not a parent or child of any of the existing coroutines.

Upon cancellation of scope1, scope2 will not be canceled. It will not affect scope2 as it is a separate coroutine. The coroutine will keep running, and this will cause memory leaks. Being mindful of how your coroutine fits in a hierarchy is essential. It will help you prevent memory leaks.

Coroutine Exceptions

There are benefits to launching a child coroutine on a scope. If it throws an exception, the coroutine will surface an exception to any handlers defined in the scope.

val scope = CoroutineScope(

Dispatchers.IO +

CoroutineExceptionHandler { _, _, _

// exception will be given here

}

)

scope.launch { ... }

scope.launch {

throw Exception()

}

If you create multiple coroutines on a scope, an exception on any one of them will cancel the other coroutines. In the example below, the three launched coroutines will cancel upon the exception.

val scope = CoroutineScope(

Dispatchers.IO +

CoroutineExceptionHandler { _, _, _

// exception will be given here

}

)

scope.launch { ... } <--- Cancel upon exception

scope.launch { <--- Cancel upon exception

throw Exception()

}

scope.launch { ... } <--- Cancel upon exception

On the other hand, if you launched a standalone coroutine, the consequence is that the coroutine will not surface an exception to the outer scope’s exception handler.

val scope = CoroutineScope(

Dispatchers.IO +

CoroutineExceptionHandler { _, _, _

// exception will NOT be given here

}

)

scope.launch { ... }

scope.launch {

val scope2 = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

scope2.launch {

throw Exception()

}

}

In this example, I launch a coroutine on scope2 inside another coroutine. This launched coroutine is standalone. When an exception occurs in it, it doesn’t bubble up to scope1. It might cause bugs or unexpected behavior. It’s beneficial to launch coroutines by inheriting the context for cancellation and exception propagation.

Supervisor Job

We saw examples above where an error in a coroutine caused its siblings to cancel. A Supervisor Job allows you to keep a parent Job running if one of the child Jobs throws an exception.

val supervisorJob = SupervisorJob()

val scope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO + supervisorJob)

val job1 = scope.launch {

while(isActive) {

delay(2000)

}

}

val job2 = scope.launch {

throw Exception()

}

val job3 = scope.launch {

while(isActive) {

delay(2000)

}

}

In the example above, the scope uses a SupervisorJob. I launch three coroutines on the scope. The second coroutine throws an exception. During this event, the other coroutines are unaffected and keep executing. The coroutines library also provides a supervisorScope.

Lifecycle Scope

We could take our knowledge and go back to the initial example to understand the coroutines’ relationships.

class MyViewModel(

repo1: MyRepository1,

repo2: MyRepository2

): ViewModel {

fun getData() {

viewModelScope.launch {

launch { ... }

launch { ... }

repo1.getData()

repo2.getData()

}

}

}

class MyRepository1 {

val coroutineScope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

fun getData() {

coroutineScope.launch { ... }

}

}

class MyRepository2(

val lifecycleScope: LifecycleCoroutineScope

) {

fun getData() {

lifecycleScope.launch(Dispatcers.IO) { ... }

}

}

A viewModelScope is an extension on a ViewModel.

val ViewModel.viewModelScope: CoroutineScope

get() {

val scope: CoroutineScope? = this.getTag(JOB_KEY)

if (scope != null) {

return scope

}

return setTagIfAbsent(

JOB_KEY,

CloseableCoroutineScope(

SupervisorJob() + Dispatchers.Main

))

}

A viewModelScope creates a scope on a SupervisorJob. As we recall earlier, it means this scope’s Job won’t get canceled if any of its child coroutines have an error.

In the example above, the viewmodelScope Supervisor Job has three decedent Jobs.

Lifecycle Scope Cancellation

fun getData() {

viewModelScope.launch {

launch { ... } <---- Job 1

launch { ... } <---- Job 2

repo1.getData() <--- Standalone Job

repo2.getData() <---- Job 3

}

}

The Job created by repo1 is not part of the viewModelScope hierarchy. When the Android framework invokes the onDestroy method of the view model, you will have to make sure to cancel repo1’s coroutine Job.

If either Job1, Job2 or Job3 throw an exception, the coroutines machinery will not cancel the parent supervisor job.

class MyRepository1 {

val coroutineScope = CoroutineScope(Dispatchers.IO)

fun getData() {

coroutineScope.launch { ... }

}

}

class MyRepository2(val lifecycleScope: LifeCycleScope) {

fun getData() {

lifecycleScope.launch(Dispatcers.IO) { ... }

}

}

In the second repository, we inject the lifecycle scope and launch a coroutine on it. Whereas, in the first repository a scope is created internally. The second approach of launching a coroutine has the benefit of keeping it to tied to hierachy you created at the view model level. You can also take an approach of creating a custom scope from the lifecyclescope and injecting into the repo.

Conclusion

I hope this article was helpful in understanding the implications of how you create coroutines. As you create coroutines, you’re building a hiearchy. The coroutines in the hiearchy have a parent, child and grandchildren relationship. It has implications on how the coroutine’s Job are cancelled as we discussed above.